CAS-2 digital case study

Discovery to Public Beta: Working on a long-term gov project

Context statement

CAS-2 (Community Accommodation Service Tier 2) digital is a project run by dxw. The service provides accommodation for those on ‘Home Detention Curfew’, those at risk of being recalled back into prison, those on prison bail or court bail. The project is about lowering the risk of reoffending and helping those who could end up homeless once they leave the prison estate. The service reduces the risk of reoffending by helping those in vulnerable situations and helps them rehabilitate as a citizen by providing housing and support. Our project focuses on improving the current referral process which involves several groups of civil servants working in prison and probation filling out a PDF form to apply for the service on the behalf of those leaving prison. The current PDF form slows down this process and causes frustrations for the users. This project is also run alongside the other tiers of CAS (CAS-1 and CAS-3), which are also run by dxw. This case study focuses on the perspective of a user researcher working on this complex project as a contractor.

Working in digital government

I worked on the CAS-2 digital project for a year, from the exploratory phase (discovery) to public beta (national rollout of the service). This is rare for a contractor, usually there is a handover period for teams or individuals between the different phases. The CAS-2 digital team mostly stayed the same so we transitioned together which gave the team a great advantage.

Working as a contractor in government can be difficult, as you need to blend into the space you’re working in, understand how things work in that government department and have contextual knowledge of the different business areas and roles. You also need to be able to collaborate with civil servants and speak to stakeholders, so that you are able to carry out the activities you need to complete your work. It is like starting a new job each time you are joining a new project. The government spaces are so large and made up of many people. Luckily, I also had the contextual knowledge from working on projects in the prison and probation space before.

User research in government

Usually the biggest barrier for user researchers is recruitment of users. This is because getting in contact with people who work in prisons is difficult as they have very busy schedules and you need to make sure that they can take time out of their day to help with user research activities. Being in contact with important stakeholders to help you express the importance of research and how it will help user’s improve their working lives is critical.

The MoJ have been working in the digital space for a long time and understand its importance. The user research community is huge and URs often collaborate and communicate when working on their individual projects. This is so they can understand constraints and different ways of working. In our project, I was able to speak to another researcher about her project and how the service connects with ours. Our users were the same people, and therefore we could learn more about their context and their problems.

Context of the Discovery phase

The first thing I make sure to do on any project is meet with our project stakeholders. This is to understand their role with the project, understand what and who they know too. This is essential for a user researcher as the stakeholders will be your ‘brand ambassadors’ for recruitment when working in government.

However, this can be different if they don’t understand the importance of user research. Even though the MoJ have been in the digital space for a long time, it doesn’t mean that the non-digital side of the MoJ understands how digital product teams work.

At the beginning of the project, all we knew was that different groups of people working in prison and probation were filling out 3 different PDF forms to send to Nacro, a charity that works with disadvantaged people.

However, we didn’t know for certain who our users were, how they filled the form in or the process around it. So how were we going to tackle this project and find out the problems with the current service?

What we did in Discovery

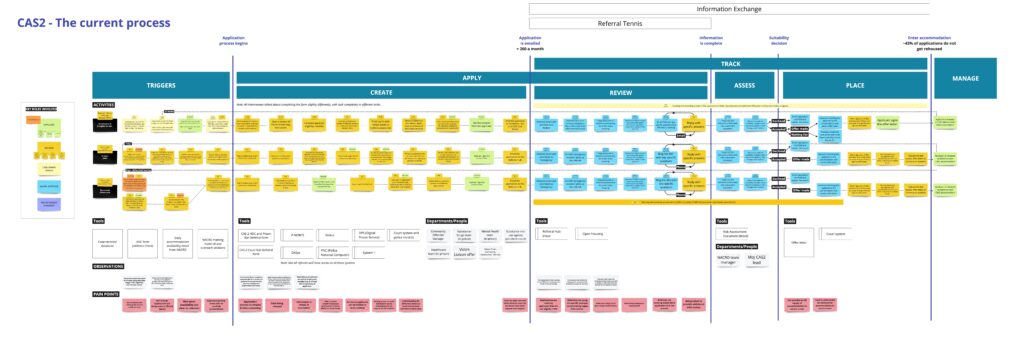

This meant our research goals were wide, we needed to make a journey map of the process from the perspectives of referrers and assessors and to understand their needs and frustrations. This was a big goal and required a lot of interviews.

From working in the MoJ space before, I knew that regions in the country can also work in vastly different ways. So we needed to ensure that we spoke to a range of people working in different prisons, those with different levels of experience and that we tried to include people from different backgrounds.

Once I had met with our stakeholders and other user researchers at the MoJ, I was able to recruit around 6 people from each user group that uses the different forms. For each user group, I ran a workshop to create their user journey maps. I did this in a group setting because it is an overwhelming process, users infrequently fill in the form and we weren’t sure about who exactly filled in the form. So we workshopped with people of different roles and experience.

Another piece of research I conducted alongside the workshops was 1 to 1 interviews. I was conscious that managers attended the workshops, so the referrers may have held back with what they thought about the process. These interviews really helped us understand the frustrations people had with the overall service, not just the PDF form. Most of the problems users faced were systemic. They included things like not being able to access printers and scanners, making a simple signature more difficult to collect from someone and send off.

After our discovery phase finished, we decided the best route to take forward was one of the forms that dealt with 70% of overall referrals. This meant our main user group was ‘Prison Offender Managers’ – they work in prisons and help prisoners with their time in prison and eventually their transition out of prison.

A journey map of the paper CAS-2 referral processes for HDC, prison bail and court bail

Context of the Alpha phase

At this point, we knew who our users were, what their main problems and frustrations were, the process they currently work in and what they had to use to submit referrals. We were now in the Alpha phase. So could we improve this process? How can we reduce the frustrations of referrers and assessors? How could we improve the chance of more people being placed into CAS-2 accommodation?

We started with the problem we knew we could resolve quickly, the PDF form. The form had formatting issues, readability issues, unclear questions and was very long. By starting here, we could easily change the problems people have with the form and therefore change the steps that happen after this.

Another problem for our users was the ‘information chasing’ after the form was submitted. Although the form is long and has a lot of information gathered in it, assessors still ask for further information because there is not enough context or the questions were never asked for in the original form. Frustrating for both parties, we hoped to resolve this by ripping apart the original form in a workshop, so we could ask the right questions in the right way. In the workshop, we went through all the questions on the original form to find what information Nacro actually needed to be able to assess someone’s suitability for a placement.

We created a prototype of the digital form, testing the riskiest assumptions. Would a digital form work in a prison setting? Would a ‘task list’ design work? Could we change how signatures for the form are collected from prisoners?

Testing the prototype

The prototype tested very well. We had many assumptions, because the prison space is complicated and different roles working in prisons all work in different ways. We found that a digital form would work as POMs work from computers in the prison office and collect information for the form either from different computer systems, different teams in the prison or from the person themselves. So they are used to switching between in person and computer research. They found having a task list helpful, they were able to see which information they would have to gather. They knew from the titles of the sections where they could find certain information. Users were also eager to click into these sections to see exactly what we were asking for, however as it was a prototype, we hadn’t made that part yet.

“Everything just seems easier to use, if I don’t know, I’m sure I can figure it out”

– Prison Offender Manager speaking in a usability test about the prototype

Going into beta

These were all good signs when we were going into the beta phase. We had a large amount of time between alpha and launching the private beta. This allowed us plenty of time to design the rest of the form, thoroughly test it with users and feed this back to the team. We were also able to research other concepts to help lead product decisions after we launched the private beta. We were in a unique situation because of this, we had time to focus on different ideas and see which could deliver value for the business and users. The developers continued to work building the form we designed and researched, we needed to think beyond that and think how we could add more value to what we were delivering to MoJ.

We researched the other user groups, which we spoke to in Discovery, to see how we could adapt our current product to fit their needs too. We learned that this user group had the same user needs and problems as our current primary user group. We also did research into an ‘admin view’ of the service, to allow those more senior to have an overview of what was happening in their prisons.

From this, I was able to summarise the findings and insights of this research to decide which piece of work we would take forward and which work we would handover to the next team working on the project. We wanted to make sure that the next team was not starting from nothing, we wanted them to have clear steps and recommendations from our team so that they could also continue delivering value.

“The new form is much more straightforward than the old paper one”

– Prison Offender Manager speaking in an observation session during private beta

A reflection

A lot has happened in a year, we went from knowing nothing to making a digital application that should alleviate most of the user’s problems.

I thoroughly enjoyed my time on the project. Most government projects are about replacing a legacy system but this was about changing a service. Taking a PDF form and digitising it, as well as trying to change the processes around it. Although our work has clearly made changes and eased user’s and the business’ frustrations, it also came with challenges.

Besides the product challenges, we also faced larger systemic problems. One of them was around recruitment, not just dealing with getting time with civil servants working in prison and probation but actually getting engagement from them about the project. Many digital projects happen within the government and some are carried out by contracting businesses. This means that the ways of working are not always the same. From working in other government departments too, there is a mistrust between these contractors and the civil servants who are the end users. Work is sometimes promised but not delivered. Or products can be made without the input of the user.

To them, we’re another team approaching them for their time and something may not even be delivered. Unfortunately, this trust has to be built overtime and progresses slowly. Towards the beta phase of the project, we had buy-in from those who had been involved in research and therefore it multiplied as we were progressing through the project towards having our beta product. This is so important for product teams working in government, people are going to trust others in their own teams who advocate for product teams like us and that’s how we get engagement and buy-in; eventually people are happy to participate in further qualitative research, fill in feedback surveys and participate in pilot phases.

There was also mistrust between our two groups of users, the referrers (civil servants working in HMPPS) and assessors (employees of the charity). During research sessions, we would hear about the problems with the ‘other side’. From referrers, it was mainly problems about assessors not reading applications properly and asking for the same information in a follow-up email. They also spoke about how time consuming and difficult it was to answer the questions on the application. The form is long and asks for information which lies in a number of different systems, and unfortunately POMs are extremely time poor because of their huge caseloads.

Assessors also had to deal with problems on their side too. The main problems they spoke about were POMs not answering questions properly, including irrelevant information on the application, and disclosing sensitive information. There was a lack of understanding from both sides.

We hoped that our new designs would help alleviate most of these problems for both groups of users as we had redesigned the questions and cut down the amount of information being asked. However, we still had work to do with the entire process of referrers and assessors working together to complete referrals.

We also faced problems with the charity we were working with. Our job was to transform the form into a digital service to work better for those working in prisons and those assessing referrals. However, change is scary, especially when you have never worked in an agile way. We were quickly testing different concepts and throwing them away if they didn’t work. We were also speaking with lots of different users about their frustrations and problems with the overall service. To the charity, we were ripping apart the form they made and showing them the problems, this was too much. We were also going to change the whole design, so their assessors needed to learn how to use the ‘new thing’.

For the most part, the charity was onboard and encouraged change. However, at times it became difficult to quickly change things like features in the service or how the questions were worded. To help ease these problems, we encouraged them to co-design with this, inviting them to different meetings and workshops so they could see why the changes were being made.

Another thing I learned was to balance the ‘mini discoveries’ within the project. We (the design team) were sometimes ahead of the developers on our team. We needed to think ahead to create different concepts to expand the service, this meant researching them, brainstorming ideas and testing them; looking back to make sure we were documenting our decisions properly and think about why we should move forward with certain design choices; and we needed to look sideways and collaborate with other teams in the MoJ to ensure our service fits within the wider context of the MoJ space. MoJ has a complicated systems map, and many teams are adding different services to help solve user’s problems. We needed to make sure that we were helping towards that, not duplicating work.

As a user researcher it’s important to be flexible with ever changing expectations or constraints. This happened a few times on the project, the scope changed or the deadline for launch was moved. As a team, we kept moving forward to see what was best for the business and the users. In research terms, this meant re-prioritising our research rounds and thinking ahead to what the UCD team should work on next. This is how we were led to conduct ‘mini discoveries’ to learn about different concepts to help lead product decisions.

At times, the project was difficult because of time constraints, expectations of clients and stakeholders and choosing what to prioritise. However, in the end we were able to change a large part of a service which was slow and frustrating for users either filling in or assessing an application form.